CATALYST

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE ONLINE MAGAZINE

Egyptian Mummy Medical Scans

How New CT Scans, Scientific Analysis Changed What We Thought We Knew About Two Ancient Lives

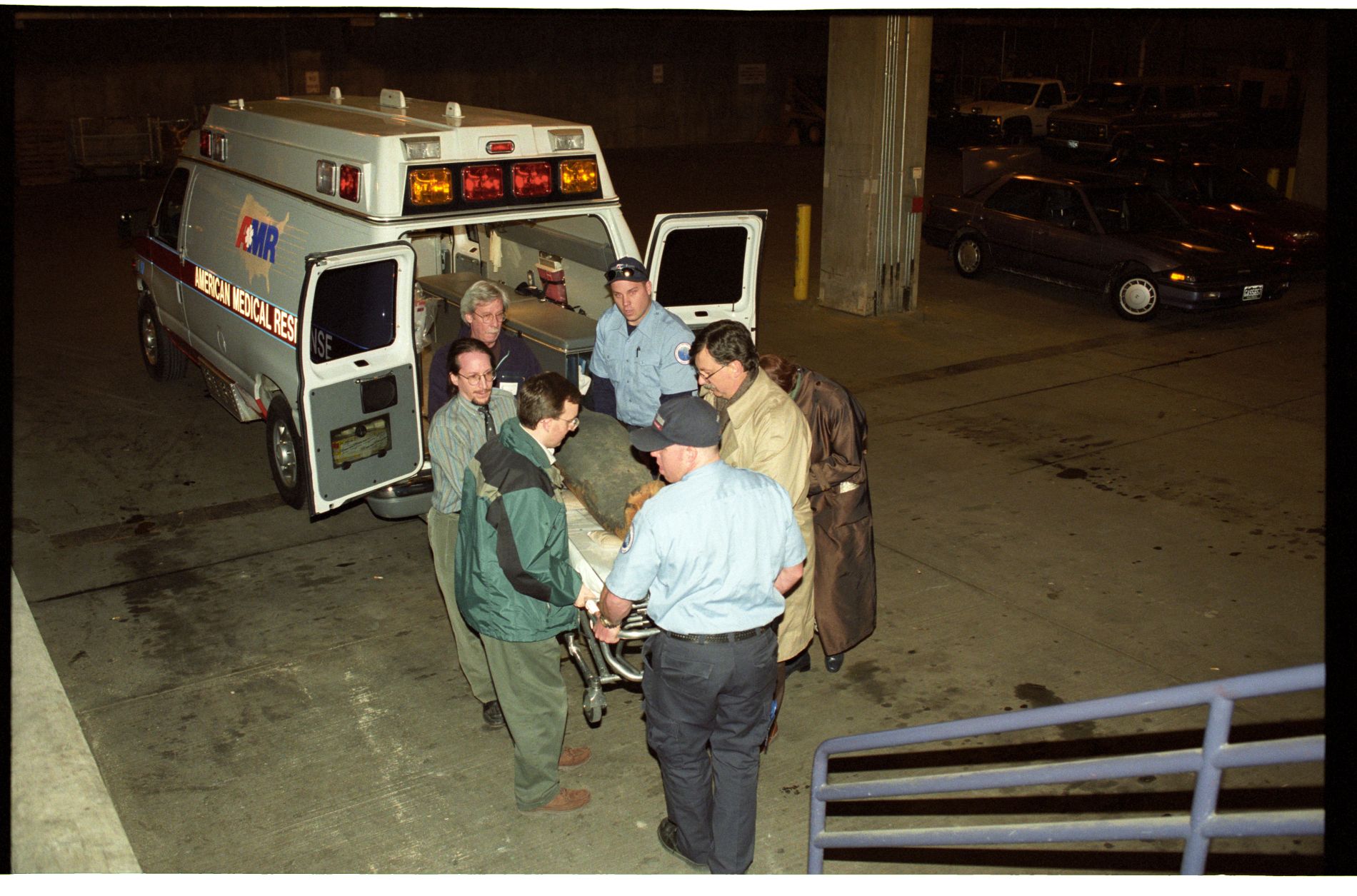

CAT scanning of Denver Museum of Nature & Science mummies at Children's Hospital Colorado in Aurora, Colo. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

The mummies and coffins you find today in the “Egyptian Mummies” exhibition came to Colorado in 1905, when Andrew McClelland, an entrepreneur from Pueblo, visited Egypt. In the early 1900s, it was trendy for wealthy tourists to purchase mummies to bring back home. The mummies eventually made their way to the Rosemount Museum collection in Pueblo and later to your Museum, where they are now on permanent loan.

The mummies were given many different names after they arrived in Colorado. So many that there is a lot of confusion in the archives. Because of this, we use their catalog numbers here. Mummy EX1997-24.1 has a black coating on the surface and EC1997-24.3 is the mummy with the exposed face.

The mummies were the subjects of a variety of past research projects, including CT scans in the 1990s. The early CT scans indicated that both mummies were females and died between the ages of 30 and 40. The scans also showed that EX1997-24.1 had various amulets and lots of packing to make her more lifelike. The wrappings of EX1997-24.3 are thinner, and there were no immediately identifiable amulets. The scans led researchers to conclude that EX1997-24.1 was rich and EX1997-24.3 was poor. When the Egyptian Mummies exhibition opened in 2000, the entire exhibit focused on the juxtaposition of "Rich Mummy" and "Poor Mummy."

The Egyptian mummies were the subjects of a variety of past research projects, including CT scans in the 1990s. (Photo/ Denver Museum of Nature & Science)

In 2016, to take advantage of dramatically improved CT technology since the mummies were last scanned, we rescanned the two mummies and one coffin using the latest advances at Children's Hospital Colorado. New tests included updated CT scans of the mummies, CT scans of one of the coffins, radiocarbon dating, pigment analysis of the paints on the coffins, analysis of the coffin wood, analysis of the style and decoration of the coffins, gas chromatography of the resins, linen analysis, isotope analysis of an eyelash of one mummy and updated conservation efforts.

The results of some these analyses are on display in the "Egyptian Mummies" exhibition and details can be found in the new edited volume published in March this year entitled "The Egyptian Mummies and Coffins of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science: History, Technical Analysis, and Conservation,” published by University Press of Colorado.

We know now from new research that the “Rich Mummy and Poor Mummy" narrative is too simplistic. Early research did not take into account the dates of the mummies. Radiocarbon dates from mummies' linens show that they died 500 years apart: "Rich Mummy" 2,900 years ago, and "poor Mummy" 2,400 years ago.

Transporting and CAT scanning of Museum mummies at Children's Hospital in Aurora, Colo. with Chad Swiercinsky, Vic Munoz, Dr. Michele Koons and Flight for Life medics. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Furthermore, the new CT scans revealed more details that help confirm their ages. EX1997-24.1 indeed has various amulets, including a heart scarab and a large plete of metal jewelry. In 2016, we also discovered the organs were removed, bundled in linen and reinserted into the body accompanied by wax figures of the Four Sons of Horus. The incision was covered by a metal plate incised with the Eye of Horus — a symbol of protection. She also has false eyes, braids or hair extensions and a wax Bennu bird — a symbol of rebirth. All of these practices were typical 2,900 years ago, which was when mummification reached its apex in Egypt.

When EX1997-24.3 died 500 years later, mummification was on the decline and there was much less care given to the internal body. It was also during this time that cartonages — papier-mâché masks over the mummy's face — became vogue. This mummy has all of her organs and the wrappings are thin. The fact that her face is exposed suggests she was partially unwrapped in the past and perhaps her cartonage was removed.

CAT scanning of the Museum mummies at Children's Hospital Colorado in Aurora, Colo. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

Our research also shows that the story of the coffins is also more complex than originally thought.

Coffin EX1997-24.2 is currently associated with mummy EX1997-24.1, but it was not originally hers. Prior to this round of analysis a reading of the hieroglyphs showed that it belonged to a man named Mes and stylistically dates to the 25th to 26th Dynasties — ca. 2,600 years ago.

Recent research by Edoardo Guzzon from the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy, found that Ernesto Schiaparelli discovered this coffin in the Valley of the Queens in 1903 in the re-used tomb of Khaemwaset, a son of Ramses Ill. In his studies, Guzzon realized that Mes' coffin was one of five left by Schiaparelli in the Cairo Museum to give to "some American museums." In the early 1900s, it was common practice to pair "nice" mummies and "nice" coffins to sell as a set to tourists. As such, the two could have been sold together to McClellend in 1905.

The new research also shows that coffin EX1997-24.4, now with mummy EX-1997-24.3, was also not originally hers. It stylistically dates to the 21st or 22nd Dynasty — ca. 2,900 years ago. Three radiocarbon samples reveal an interesting story. The dates from wood samples are similar — ca. 2,900 years old. The coffin wood is 100 years older. This suggests that it was made from previously used wood. The overall construction is poor but the decoration is high quality, indicating that it was not expected to last particularly long — likely due to high levels of tomb robbery at the time. Because of this, it is possible that EX1997-24.3 was originally buried in this coffin even though she died 500 years after it was made. It is also possible that she was placed in this much older coffin for the tourist market in early 1900s. To confuse matters more, the other mummy (EX1997-24.1) may have actually been buried in this coffin and switched to Mes' coffin sometime over the last century in Pueblo. Both are covered with a thick black substance and both are 2,900 years old.

CAT scanning of the Museum mummies at Children's Hospital Colorado in Aurora, Colo. Scanning and access made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. (Photo/ Rick Wicker)

We may never know the answer to this complex puzzle. Nonetheless, the recent research has revealed new and fascinating stories for these old friends of your Museum.

Overall, the new research indicates that the differences we see between the two mummies was less about their economic status and more on their place in the history of Egyptian mummification.

----

From the ancient past to the present day, from land to sea to sky, the Denver Museum of Nature & Science offers an unparalleled opportunity to discover and explore the wonders of the natural world that surrounds us. Come visit us at the Museum!

Ready to explore more?

Plan your visit and see the wonders of nature and science up close. Get your tickets today, or become a member for unlimited admission, exclusive events and a full year of discovery!