Hidden on the third floor of your Museum is a secret, super-powered science lab

This small but mighty operation, known as the Digital Research Laboratory, is filled with powerful computers, a 3D printer, and a menagerie of multicolored fossil models. While the Museum’s paleontologists dig for bones outside in the sun, the scientists in the lab are also busy extracting bones—but from X-ray computed tomography scans, or CT-scans, of rocks and unprepared specimens.

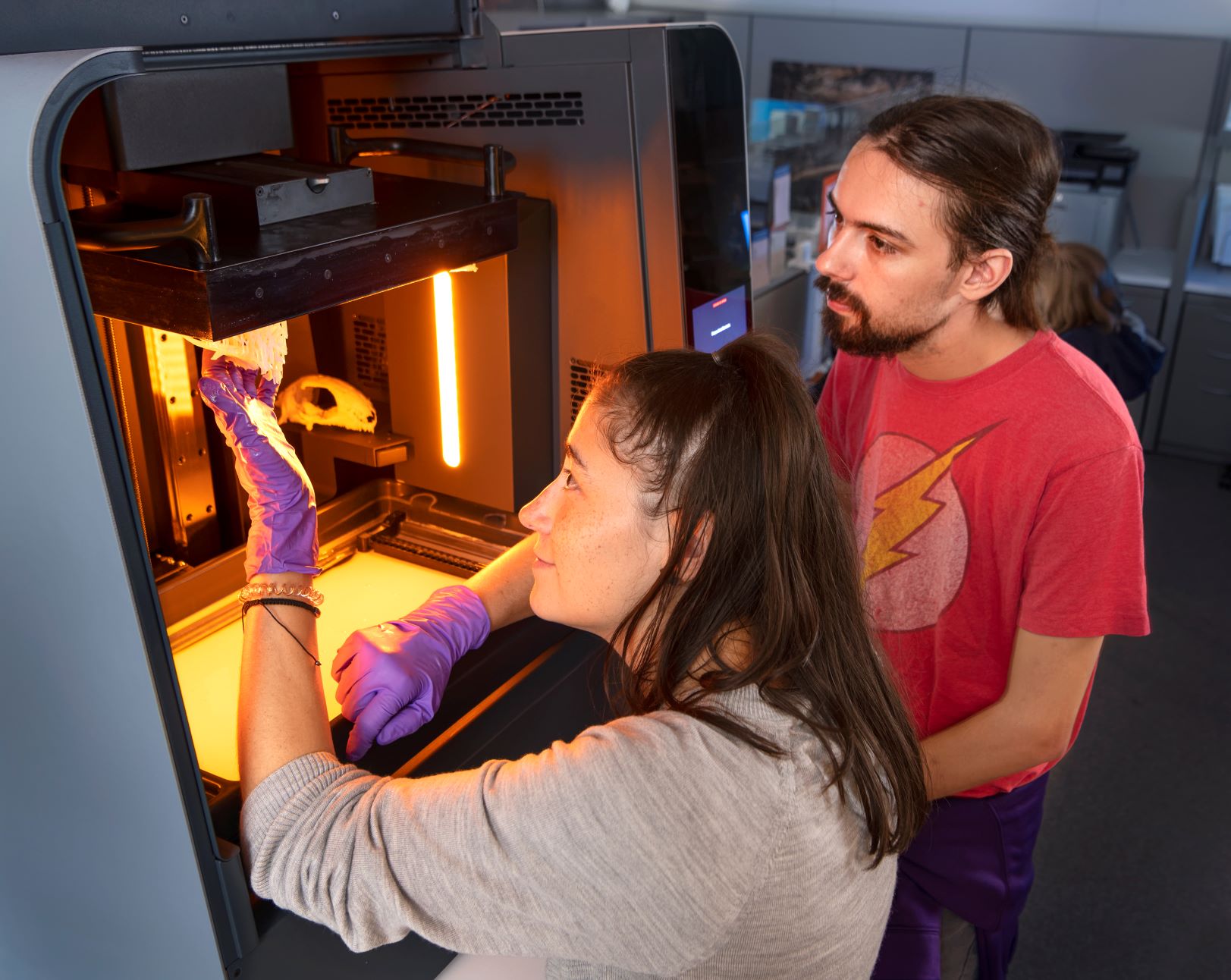

Lindsay Dougan and Eldon Panigot reviewing 3D printed models in the Digital Research Lab at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

X-ray computed tomography is a non-destructive imaging method, most commonly used in a clinical setting, which generates a stack of thousands of black and white images with a wide range of ‘grayscale values’. Each grayscale image represents a single cross-section or ‘slice’ through the specimen. The various shades of gray in these black and white images represent differences in the density of various portions of the scanned object. In the DRL, we use these CT images to find and even peer inside fossils to visualize previously hidden anatomy, without ever damaging the specimen.

As we survey these CT slices, we digitally ‘paint’ different elements of each skeleton with a ‘mask’, eventually creating a three-dimensional model of each skeletal element. These digital pieces can be assembled and virtually dissected like a 3D jigsaw puzzle, allowing us to non-destructively visualize features that are not visible on the surface. We have uncovered information about key soft tissue structures such as size and shape of brain cases, confirmed the presence of extra tooth rows in a 250mya turtle ancestor, even identified a juvenile mammal from Corral Bluffs based on the presence of deciduous and permanent teeth developing in the upper jaw!

Perhaps the most iconic example of such digital discovery is from our very own Corral Bluffs, Colorado. In an analysis of the large, beaver-sized mammal, Taeniolabis, we modeled the space within its inner ear, a never-before-seen area that is typically inaccessible to traditional preparation techniques like those used in the preparation labs at the end of the Prehistoric Journey exhibit. We created a virtual cast of the tiny labyrinth that once held this animal’s hearing and balance organs, and revealed features of the hearing organ that tell us this animal had a limited hearing range similar to birds and reptiles, very different from us humans! We can’t wait to model the rest of the new-to-science fossils and coming out of this deposit.

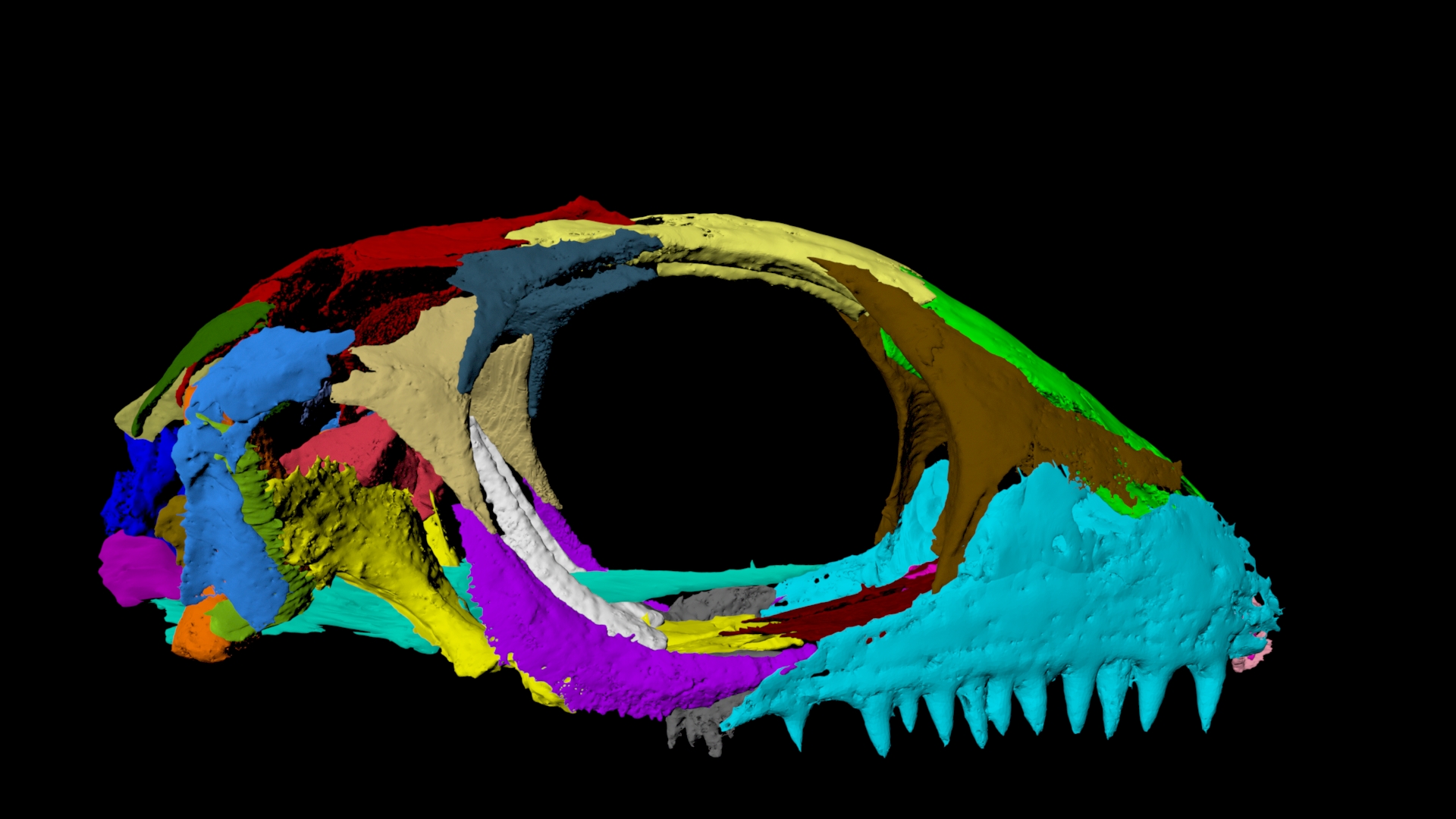

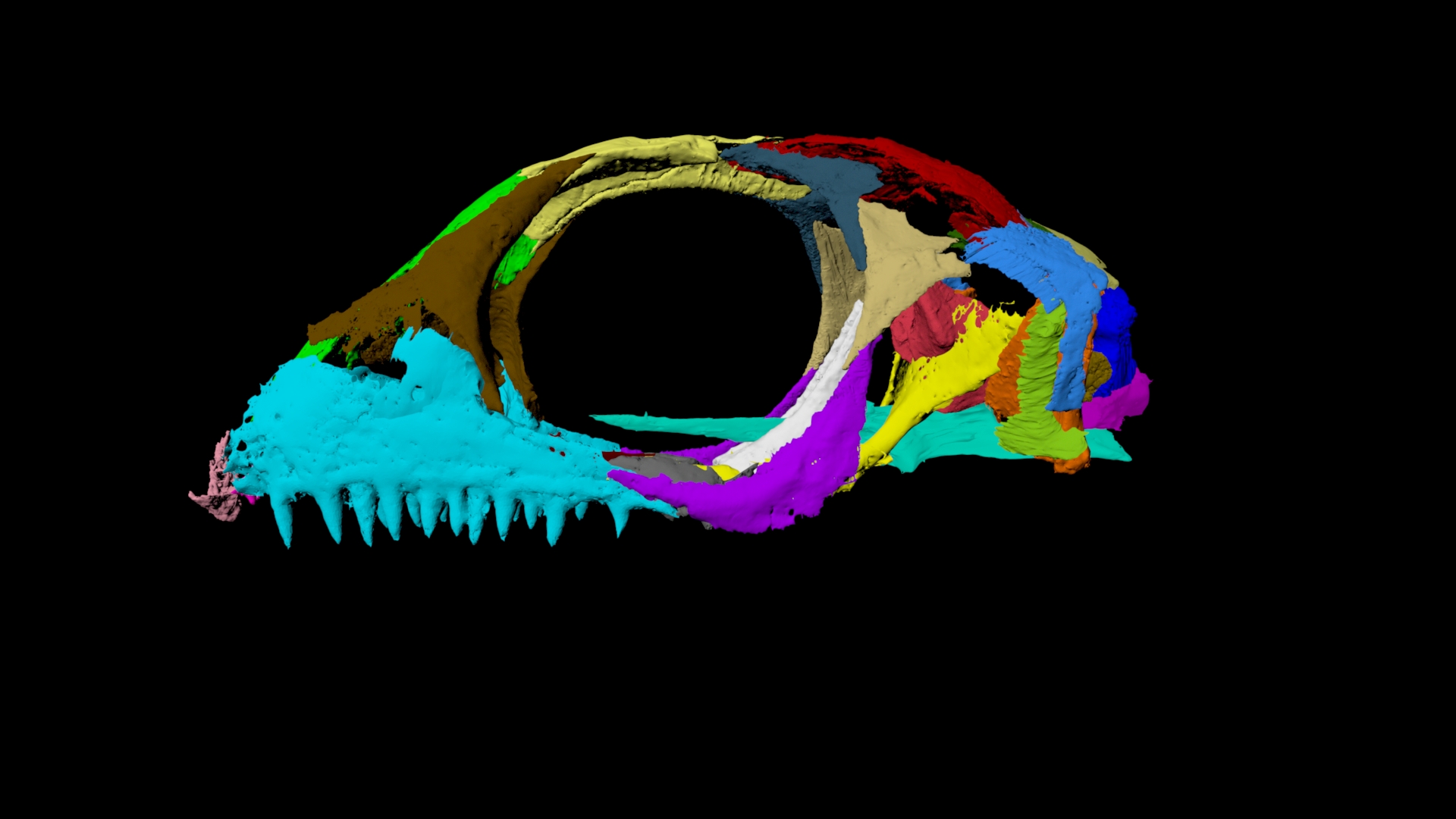

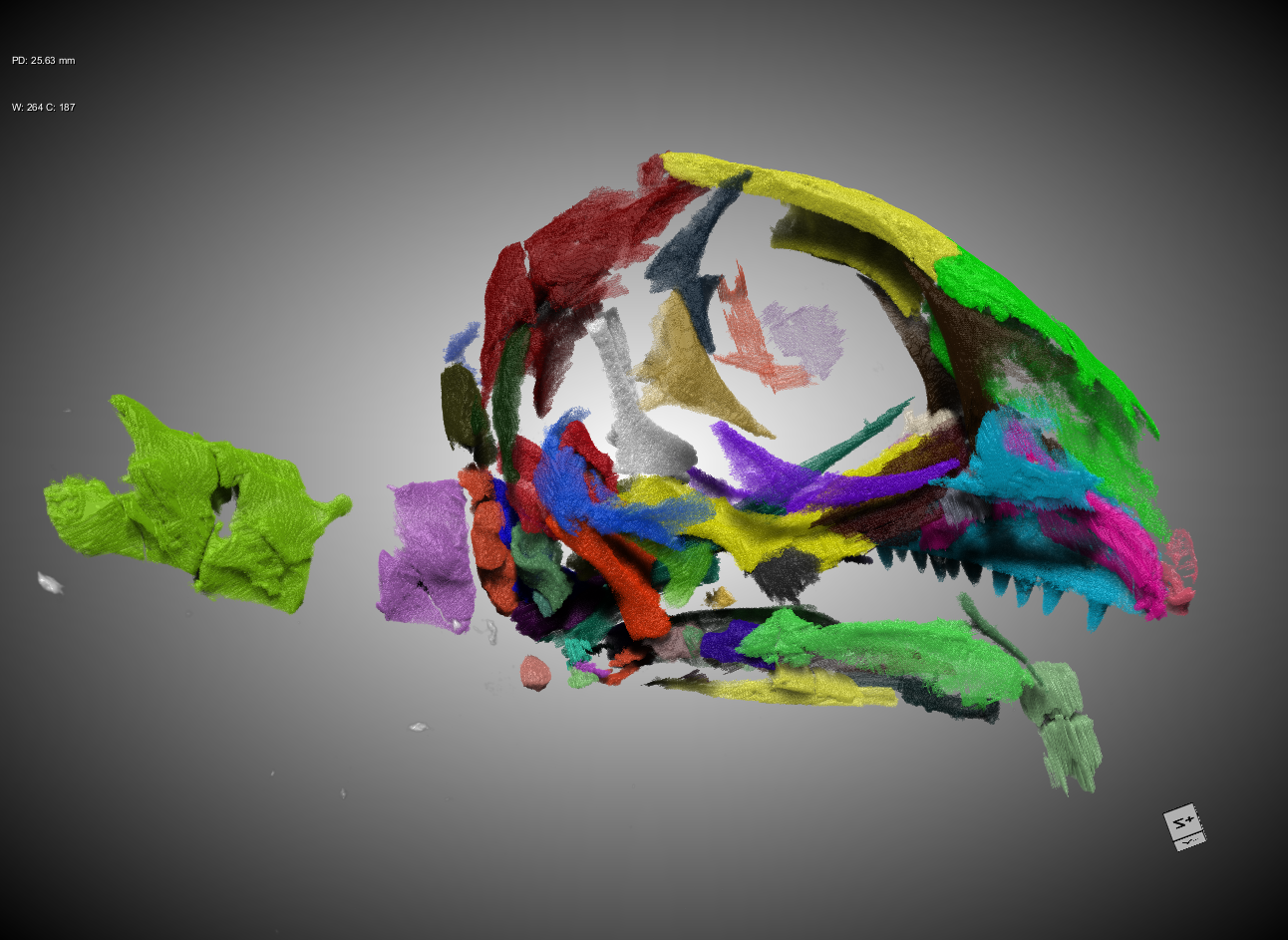

Using software developed for the animation industry, we can also digitally repair damaged fossils by replacing missing bones, reconnecting broken pieces, and moving loose elements back into place. For example, although the right side of the skull of this in the new-to-science fossil reptile had been crushed, we were able to reconstruct and digitally replace its deformed and missing elements. The resulting model, shown below, illustrates what the animal’s skull may have looked like before death and burial.

The unnamed, new-to-science reptile skull after reconstruction and realignment.

The unnamed, new-to-science reptile skull after reconstruction and realignment.

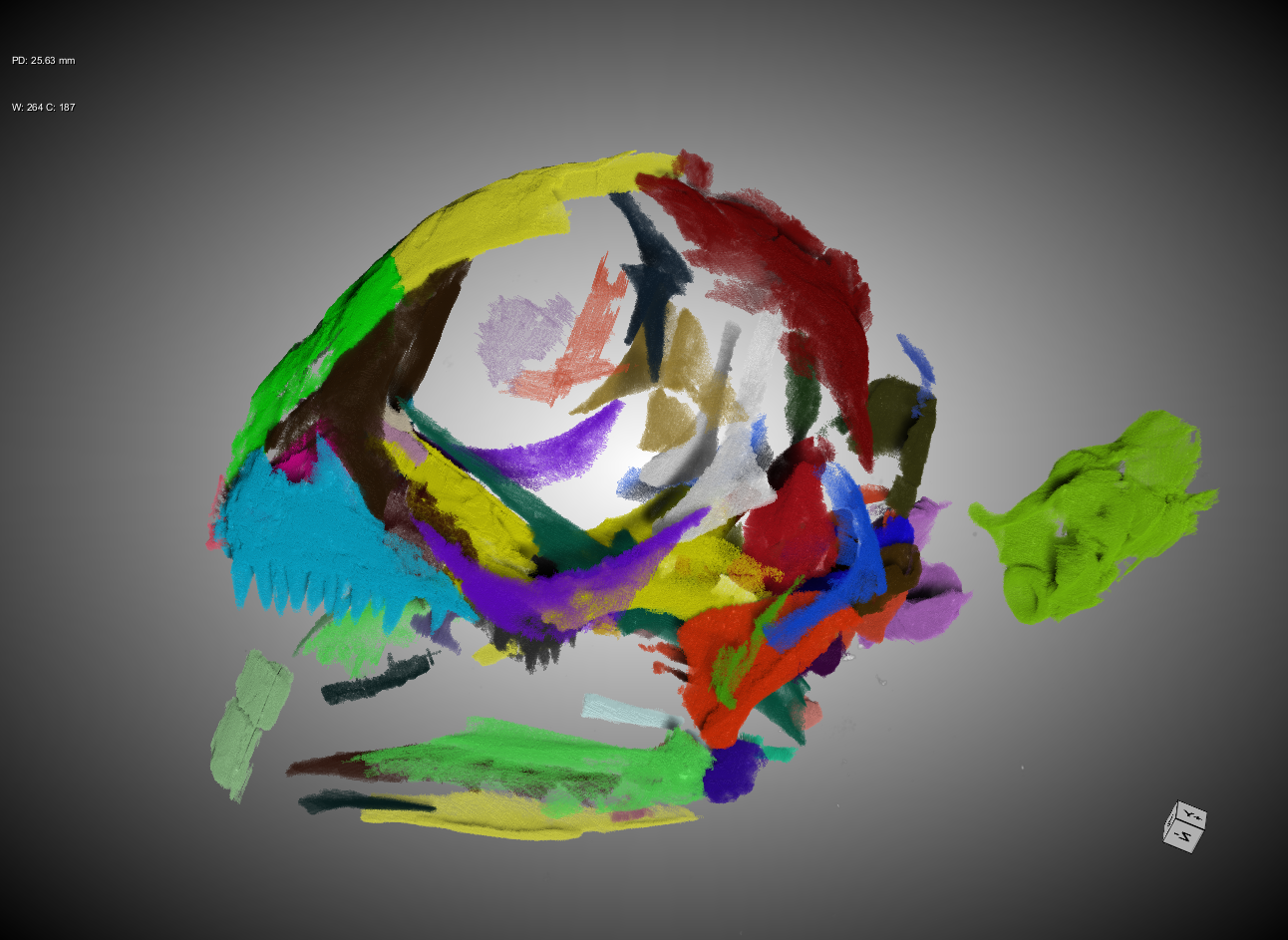

CT data of the unnamed, new-to-science reptile skull specimen as it was found in the rock before reconstruction.

CT data of the unnamed, new-to-science reptile skull specimen as it was found in the rock before reconstruction.

Virtual modeling is just one product of the Digital Research Lab. We also make 3D prints of our models onsite. By printing different versions of models as we work through reconstruction, we can ground truth our digital masking of each skeletal element. It also allows us to increase the size of tiny specimens so we can see fine details of bones; or in the case of huge skeletons, to shrink them to make more portable models—such as our pocket sized fossil crocodile! Such 3D prints allow us to test the viability of hypothesized arrangements of fossil bones, and to visualize structures that are nebulous in 2D image slices. Not to mention such models are fantastic for public outreach and engagement, because they are less easily broken and amenable to hands-on activities. No doubt some of these models will be coming to an exhibit or school near you, and soon!

The most exciting thing about the lab is that it, and other such labs around the world, have revolutionized paleontological research: we are repurposing an existing imaging modality to reveal parts of fossils that were previously rarely seen and therefore less studied.

Learn more from Lindsay about how the Digital Research Lab helped figure out where turtles fit into the story of evolution.