I was stunned and in disbelief at what I saw. It was 2002, three years after we had collected a 150-pound plaster jacket from some Cretaceous rocks on the island of Madagascar. When collected, it was thought to contain only some scrappy, associated bones of a fossil crocodile. Not a high priority. Relegated to backlog.

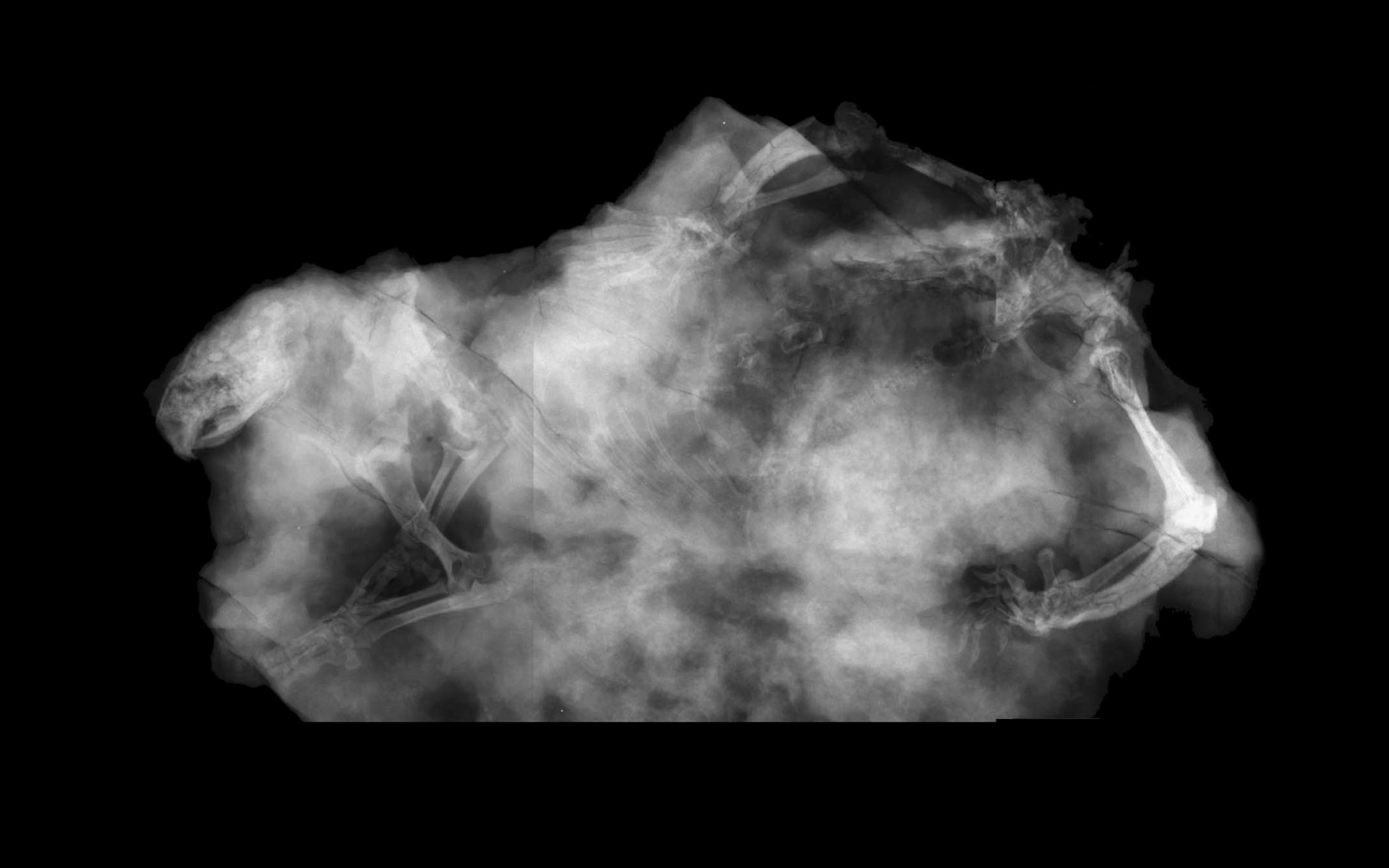

But there it was, deep inside the plaster jacket: something different. Beneath the crocodile bones, the fuzzy outlines on a series of X-ray images of what looked to be a complete, well-preserved skeleton of a 66 million-year-old mammal. The skull and front part of the skeleton were in undistorted alignment, entombed as if in mid-step, but the right hind limb was askew and the tail was strangely tucked under the body.

It was the discovery of a lifetime! My mind racing, I didn’t sleep for the next two days.

Fast forward 18 years. In late April, we announced the discovery of this new mammal in Nature, arguably the world’s top scientific journal. The specimen on which it is based is the most complete skeleton of a Mesozoic (roughly 250-65 million years ago) mammal from the entire southern supercontinent of Gondwana, a landmass torn asunder by plate tectonics during the Cretaceous into what became South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, the Indian subcontinent, and several smaller bits including Madagascar.

BUT WHAT IS IT?

The skeleton is beyond bizarre. The skull has four (instead of two) rodent-like upper incisors and molars, the likes of which are unknown in any mammal, extinct or living. The bones of the snout have more holes (foramina) than any known mammal, holes that served as passageways for nerves and blood vessels supplying a snout covered with whiskers. There is one very large, midline hole on the top of the nose for which there is no parallel in any known fossil or living mammal. We have no idea what it was used for!

The bizarreness is also evident in the skeleton behind the head. The spine, for instance, has more vertebrae than any Mesozoic mammal, the tail is extraordinarily short, and the shin bone is strangely curved. The list of anatomical oddities goes on.

About the size of a Virginia opossum (~7 pounds), the skeleton is also unusual in that it was very large for its time. Most mammals that lived alongside (or between the toes of) dinosaurs were much smaller—mouse-sized on average. The many bizarre features of this mammal, led us to name it Adalatherium, which, when translated from the Malagasy and Greek languages, means “crazy beast.”

Looking beyond the uniquely bizarre attributes, we ultimately determined that Adalatherium belongs to an extinct group called gondwanatherians, so named because they are only known from Gondwana. Gondwanatherian fossils were first found in Argentina in the 1980s, but have since also turned up in other parts of South America as well as in Africa, India, the Antarctic Peninsula, and Madagascar. Gondwanatherians were an early evolutionary experiment in mammalness, an experiment that was snuffed out in the Eocene, about 45 million years ago.

What took so long?

Despite the initial excitement, patience—a LOT of patience—was required to determine that Adalatherium was a gondwanatherian and to document its anatomy. This required months-long, fine-scale mechanical preparation following by state-of-the-art micro-CT scanning and many thousands of hours of digital postprocessing. A bit of luck was required, too. We were really quite stumped by the many bizarre features of our crazy beast; much of the skeleton was unlike that of any known mammal and therefore, there was nothing to meaningfully compare it with.

Prior to the announcement of the nearly complete skeleton of Adalatherium, gondwanatherians were only known from a handful (no exaggeration) of isolated teeth and jaw fragments, with one critically important exception. The exception was a discovery made in 2010 by my then-Ph.D. student Joe Sertich, now Curator of Dinosaurs here at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. Working at a relatively remote Madagascar site where fish fossils were in abundance, Joe made the prescient decision to collect several large blocks of fossiliferous rock rather than quarry the rock on-site.

Once back in the lab, we CT-scanned the blocks and, lo and behold, in one corner of one block, in addition to many fish bones, was a mammalian cranium. Based on its teeth, it was identifiable as the cranium of a gondwanatherian, the most complete specimen of a gondwanatherian then known to science, and the largest known Mesozoic mammal from Gondwana (~19 pounds). We described this new gondwanatherian in 2014 and named it Vintana, which means “luck” in the Malagasy language, immortalizing the serendipitous nature of its discovery.

Vintana, as luck would have it, proved to be the key to understanding that Adalatherium was also a gondwanatherian. Even though their molar teeth are quite different, their bizarre incisors are very similar and many aspects of the snout are virtually identical. With the discovery of the complete skeleton of Adalatherium, we now had insights into what an entire gondwanatherian might have looked like and how it might have lived –– a large, active, plant-eating, possibly burrowing mammal, with keen senses of hearing and smell and a very sensitive snout.

Why Madagascar?

Science is driven by questions, and I had long been fascinated by the mysterious origins of the highly endemic fauna of terrestrial, backboned animals of Madagascar, the fourth-largest island in the world. How did they get to the island, when did they get there, and from where did they come?

Today, the island is home to many animals (and plants) found nowhere else on the planet, including hissing cockroaches, giraffe weevils, tomato frogs, Satanic leaf-tailed geckos, panther chameleons, and streaked tenrecs to name a few. And, of course, there is the signature group of mammals — lemurs — made famous in the animated “Madagascar” movies. Only a few thousand years ago, the Madagascar vertebrate fauna also included 1,400-pound elephant birds, gorilla-sized lemurs, and pygmy hippopotamuses.

In evolutionary terms, islands are the stuff of weirdness. It is on islands where animals evolve in isolation, often for millions of years, with different food sources, competitors, predators, and parasites. Indeed, different everything compared to mainland species. As a result, they develop into different shapes and sizes and evolve into new species that, given enough time, spawn yet more new species.

My research is focused on fossil mammals, so my hope when I started the Madagascar project in 1993 was to find early mammals on the island, perhaps even the precursors of lemurs and tenrecs.

I learned that some Late Cretaceous fragmentary bones and teeth of dinosaurs, crocodiles, and turtles had been discovered by a French soldier, Adjutant Landillion, in 1895. That was all I needed to fantasize that we could potentially also find mammal fossils. But the odds were extremely low. Indeed, in 1993, there were only two mammal sites of undisputed Late Cretaceous age, a vast swath of 34 million years, on any Gondwanan landmass — one in Argentina that had yielded approximately 50 isolated teeth and jaw fragments and one in India that had yielded five isolated teeth.

After many days of travel involving long flights and layovers, administrative and logistical hurdles, unimaginably bad roads, and several vehicle breakdowns, we arrived in the dead of night on July 19, 1993, in the same area where Landillion had made those initial discoveries. With boots finally on the ground, the discovery of Late Cretaceous mammals on the island of Madagascar took only 20 minutes early the next morning at the first patch of rock outcrop we stopped to survey, about a quarter-mile from where we had pitched our tents.

That first specimen, a fragmentary worn molar, could not be identified beyond some indeterminate mammal and, unfortunately, as the minutes of that first field season turned to days and then to five weeks, we found no more mammalian specimens in the surrounding strata.

That’s the bad news

The good news is that we found the remains, including skulls and skeletons, of a broad array of other vertebrate animals: fish, frogs, turtles, snakes, lizards, crocodiles, non-avian dinosaurs (both large and small), and even birds.

Now, after 12 more expeditions to these same rocks, we have collected over 20,000 specimens. But mammals are represented by a total of only 12 specimens –– nine of them isolated teeth, one a fragmentary femur, the cranium of Vintana, and the complete skull and skeleton of Adalatherium embedded in that plaster jacket discovered in 1999. (Incidentally, it turned out that there was another unexpected find: a hatchling crocodile at the bottom of the same plaster jacket. Adalatherium was the filling in a crocodile sandwich!)

Adalatherium is the epitome of weirdness and now stands as the best example of mammalian island endemism during the Mesozoic. But anatomical uniqueness is also vividly expressed in a number of other vertebrates that we have collected from the same strata: a massive, armored predatory frog that we named Beelzebufo, the devil toad, large enough to have conceivably eaten hatchling dinosaurs; a three-foot long crocodile named Simosuchus that had a pug-nose, and clove-shaped teeth adapted for eating plants; and a small theropod dinosaur named Masiakasaurus with strange buck teeth that point forward.

Madagascar became an island approximately 88 million years ago when the Indian subcontinent detached from Madagascar’s eastern coast and began its migration through the Indian Ocean to ultimately collide with Eurasia. Marooned, the newly isolated vertebrates of Madagascar adapted to their new, much smaller island environment. Overall, the vertebrate fauna from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar is a Mesozoic assemblage of creatures that parallels some of today’s island faunas in their uniqueness.

Interestingly, none of the vertebrate animals we have discovered in the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar appear to be ancestral to anything on the island today.

Molecular science corroborates our negative evidence, suggesting that the ancestors of the modern-day mammals, including lemurs and tenrecs, arrived after the end of the Cretaceous, presumably by fortuitous rafting to the island on huge mats of vegetation storm-washed into the Mozambique Channel from large East African rivers. That is the current working hypothesis. The quest for more evidence in the form of fossils both earlier and later in time continues.

Listen to the Story

In evolutionary terms, islands are the stuff of weirdness. It is on islands where animals evolve in isolation, often for millions of years, with different food sources, competitors, predators, and parasites…indeed, different everything compared to mainland species. As a result, they develop into different shapes and sizes and evolve into new species that, given enough time, spawn yet more new species. Listen to Dr. David Krause discuss this new discovery in this podcast.

Come see this bizarre beast for yourself!

The skeleton of Adalatherium and other vertebrate animals from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar are currently on display in a temporary exhibition on the 2nd floor of the Museum on the bridge between the Phipps IMAX® Theater and the wildlife halls.