The oldest trilobites in the world lie in a cold, metal drawer 42 feet below the Museum’s main floor.

These 520 million-year-old “cockroaches of the sea,” along with a trove of other scientifically impactful specimens, are the donated legacy of the late Stew Hollingsworth (pictured here). With the help of Bureau of Land Management funding, our team has been unraveling the secrets of this massive collection, revealing information that not only speaks to science, but to a core Museum value—relationships.

Like many of us, Hollingsworth had a hobby. The son of an oilfield biostratigrapher, he began collecting fossils when he was eight years old. By day, he was a mining geologist, but every morning before work he would spend a couple of hours studying fossils in his home office.

When Hollingsworth retired in 1990, he launched into his hobby with fervor, transforming his passion into a full-time vocation.

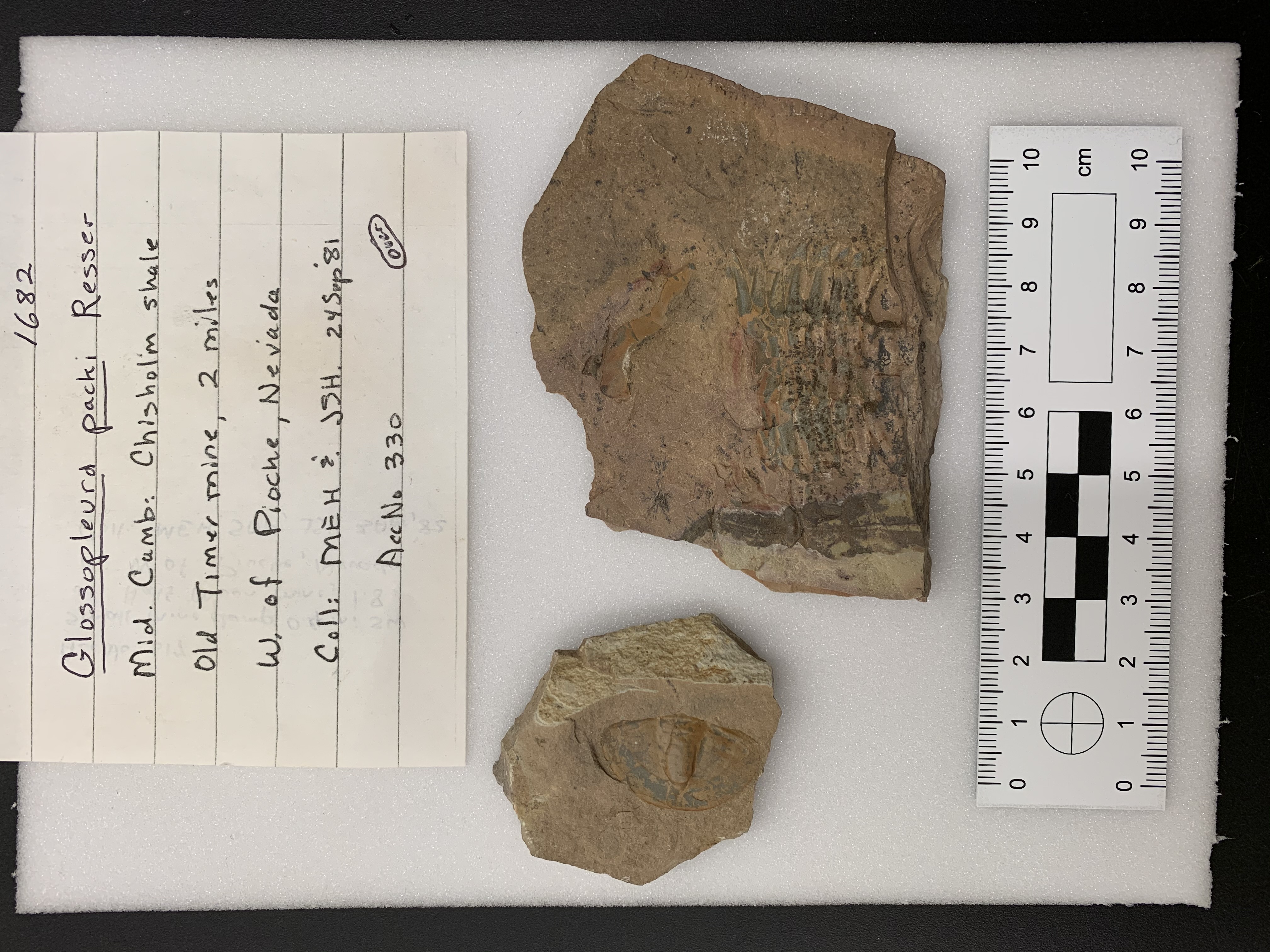

In the process, he became one of the world experts on Cambrian trilobites—marine arthropods that dominated oceans for over 250 million years, and whose carcasses are lynchpins for understanding evolution, deciphering environments and telling geologic time. Hollingsworth published a dozen peer-reviewed papers, named 11 species and five genera, and documented the successive changes in trilobites that helped define three international time periods. The fossils that he published articles about are at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, but all of his unpublished material, including his worldwide reference collection of Cambrian trilobites and his personal (i.e., just for fun) collections, are housed in your Museum.

The volume of material is immense, but unlike most collections that are offered to the Museum, the provenance, or origins and context, for each specimen in the Hollingsworth collection has been meticulously documented in his field notebooks.

This provenance information makes this collection scientifically valuable. It allows the unpublished materials to be catalogued and made available for research. Such as the trilobites Hollingsworth and his wife Mary (herself a talented collector) discovered in the Campito Formation of Nevada. These might be the oldest on Earth!

Collection items being unpacked at the Museum.

The Hollingsworth collection also illustrates the broader impacts of science. For example, this collection’s ledgers brim with examples of the relationships that empowered Stew’s success. Like most community scientists, Hollingsworth had to do science without benefit of the resources and backing of a large institution, so it was his relationships that allowed him to succeed, and in many cases blossomed into collaborations.

One of the earliest examples, now in the Museum’s archives, is a letter, signed with love, from his father. It asks which of his own specimens he could offer to help Hollingsworth jump start his emerging paleontological career. There is also correspondence with colleagues and friends from China to Russia, and even with a local furniture store owner—all of whom provided scientifically useful specimens, advice and literature to Hollingsworth. This collection thus embodies the realized potential of Hollingsworth’s diverse and collaborative team—one that grew from cultivating relationships.

Collection items being unpacked at the Museum.

This legacy continues as we organize, rehouse and begin to use the collection. For example, last year Hollingsworth’s basketball-sized ammonite fossils inspired two interns to connect paleontology with American history. They celebrated our newest holiday, Juneteenth, with a hands-on display on the 2nd floor mezzanine, in which huge ammonites, creepy trilobites and other deep-time Hollingsworth beasts were touchable by visitors of all ages. Staffed by interns from across the Earth sciences department, these next-generation scholars encouraged our community to make connections between ancient and modern environments, with an eye to the future. Such collections and activities are catalysts, reminding us that science is a collaborative effort that we can all participate in—one that is underpinned by relationships.

Watch Museum collections management interns, Alexis and Sarah, discuss Juneteenth along with fossils in our collections that roamed Texas millions of years ago. See how Colorado, the Museum and Black history all connect.

OH, BY THE WAY

Congratulations, James!

Curator of Geology James Hagadorn received the Outstanding Scientist Award for 2021 from the Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists. Head over to Facebook for a collection of his 60 Second of Science clips to see some of the many reasons why James earned this recognition.