Behind the scenes of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science is one of the most exciting labs in Denver

The Zoology Preparation Lab specializes in dissecting and preparing vertebrates for the zoology research collection. Here, you’ll find dozens of Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) that were killed by cats, over fifty shrews (Sorex sp.) from Wyoming preserved in ethanol and the newest addition—an endangered mountain tapir (Tapiris pinchaque) skeleton from the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. Working to ensure these specimens are preserved to last is a zoology preparator, a team of volunteers ready to get their hands dirty and a crew of flesh-eating beetles (Dermestes maculatus) itching to eat flesh off of skeletons.

Although few people prefer to work in dissection, zoology preparation labs are the lifeblood of an active zoology collection. Preparators are responsible for ensuring specimens will last centuries for future generations of scientists to study and the public to see.

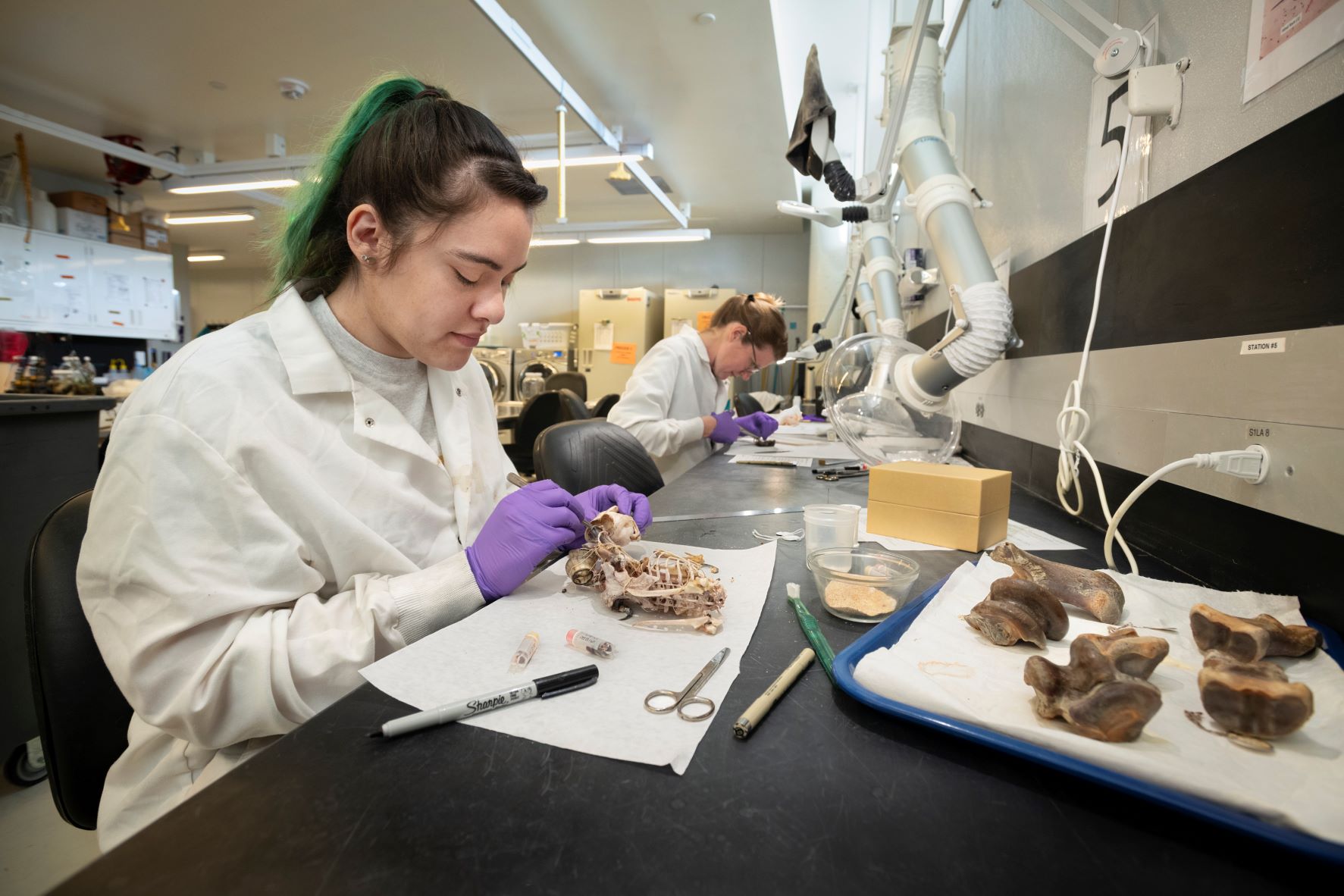

Zoology Preparator, Andrea (Andie) Carrillo, prepares specimen.

Every part of an animal we keep speaks a new story

Analysis of a feather shows us how a bird migrated or what it ate. A clean skeleton gives us information on how an animal moved. Sampling liver can tell us what toxins were found in an animal’s environment or how its related to other species.

Zoology collection preparation did not start with the founding of the Museum in 1900. Natural history collections started in Europe in the 1600s as “cabinets of curiosity.” They held animal specimens and cultural objects taken from regions that were newly colonized by Europeans. These cabinets quickly grew in popularity, size and scientific rigor. They became so popular in the 1800s, that many major U.S. cities, including Denver, started their own collections to record biodiversity in their region, support scientific research and engage the public.

Famous scientists like Charles Darwin used prepared skins to study and document evolution

Darwin used a now common method of round skin preparation to provide proof of the differences between species and to support his theory of biotic evolution. Even today, one criterion for naming a new species is having a physical record of a specimen, also called a type specimen. Specimens from Darwin’s famous Galapagos finch and mockingbird studies are still in museum collections around the world.

Although preparation has been around for hundreds of years, the role of preparators has changed significantly with time. Natural history museums have a long history of hunting animals for display in taxidermy dioramas. We no longer have an in-house taxidermist and the animals we prepare now come from other sources. Today, we mainly acquire animals though wildlife rehabilitation centers operating along the Denver Front Range. Wildlife rehabs come across thousands of animals a year that die naturally or from human-caused injury.

Every year, we keep hundreds of animals brought to wildlife rehabilitation centers by concerned Coloradans that were killed by pets, cars or buildings, and we preserve them and their data. With the work of the lab, we can give these animals a second life as research specimens. They provide information that has the potential to lead to discoveries about wildlife or help with the conservation of their species. With the help of scientists, students and other curious individuals, the data we collect and the parts we prepare have the potential to explain current and future questions about the natural world.

I invite you to visit the zoology section of our website at dmns.org/science/zoology to explore more.

Specimen being prepared inside lab.

One More Thing

Your Museum reaches school communities with ExciteEd!, student and teacher educational programs. Whether it is at the Museum, in a classroom or virtually, students experience the excitement and fun of nature and science through hands-on learning. Teachers build skills in our professional development programs, where they learn about best practices in science education and how to integrate hands-on science activities into their classrooms.

What teachers are saying about our programs:

“Students had an engaging, hands-on experience that perfectly fit with the unit we are studying.”

"I love that I can use the tools presented in the professional development course right away in my classroom!"